From cSquares to cStories: Communication in action

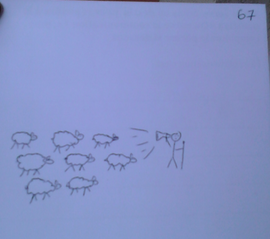

The "shepherd-flock" effect

The "shepherd-flock" effect

We took the draw and write technique a step further by asking the students to construct a story from the collection of cSquares. The aim was to find sets of drawings that shed light on complex communication phenomena in the society. This exercise took place towards the end of the course (second to the last class), hence after the students had received the course content on Theories of Communication in the meantime.

Students were asked to form small groups of 3-4 and to select the cSquares that inspired them to write a story of communication. In 2015, 24 groups were thus formed. During the second the second to the last class, we displayed the whole set of 74 cSquares on tables as exhibits and students viewed them during a two-hour period. They were at liberty to select any number of drawings provided they could find way of articulating a story or a path amongst the selected drawings. Students discussed amongst members of their groups and took snapshots of some cSquares. They were free to ask the instructor any number of questions about the aim of the exercise which they found a bit puzzling at first. Most of the questions focused around:

“what the story should be about, whether it had to about something real or make-believe” (to which I replied that it was to be plausible);

“how many cSquares should they choose?” (to which I systematically responded that it was up to them). The story could portray communication situations that they are aware of in everyday life, either through the media or through personal experience or could exemplify some of the communication theories they had heard of or learned of during the course.

Students then had one week to work on their storyline outside of the class. During the last class, they presented their stories in front of their classmates.. Each group had 10 minutes maximum to stage and tell their story. they could use any type of props and presentation material (powerpoint slides, videos, staging, role plays, etc).

The presentations were not filmed.

The 24 stories constructed from the 74 cSquares collected in 2015 illustrate how students were able to articulate a path among the depictions of communication in order to make convincing statements and narrative about the role of communication in society. For reasons of space, it is not possible to reproduce the entire sets of slides used in the 24 presentations nor to reproduce the stories in their entirety. However, we obtained the written scenarios of the stories which struck us as particularly well articulated, striking or creative. We note that in particular, cSquare 67 proved to be popular since it featured in many of the stories whereas the execution of the drawing is rather tentative, schematic and not particularly striking. This drawing conveyed a popular belief about the social function of communication that captured the imagination of many students. It showed a shepherd holding a staff and using a loudspeaker to call his flock of sheep to attention who then follow him. This is clearly an allegory of the hypodermic syringe or the functionalist-behaviourist theory of the mass media defended by Harold Lasswell (1927) to which Paul Lazarsfeld (1944) brought a nuance by postulating the two-step-flow model of communication which states that people's opinion are more influenced by intermediaries (circles of friends, families, co-workers, opinion leaders). However, later studies by McCombs and Shaw’s on the Agenda setting theory (1972) of the mass media reaffirmed their influence on public opinion. The drawing portrays the unidirectional model of communication as a powerful tool for propaganda and persuasion in the hands of opinion leaders or of the mass media. The flock of sheep here represent the masses who adopt the views of those perceived as opinion leaders rather than form their own.

Underlying this seemingly simple depiction is the psychology of the crowd which has been well studied in behavioural sciences, since the late 19th century (Gustave Le Bon 1895). Fiction and literature have also given us many memorable illustrations. Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar famously portrays the very fickle nature of public opinion which was constantly swayed by the last orator.

Below is a translated and abridged version of two of the most remarkable story lines that were presented in our 2015 storytelling activity using this collection of cSquares.

- Instructions and set-up

Students were asked to form small groups of 3-4 and to select the cSquares that inspired them to write a story of communication. In 2015, 24 groups were thus formed. During the second the second to the last class, we displayed the whole set of 74 cSquares on tables as exhibits and students viewed them during a two-hour period. They were at liberty to select any number of drawings provided they could find way of articulating a story or a path amongst the selected drawings. Students discussed amongst members of their groups and took snapshots of some cSquares. They were free to ask the instructor any number of questions about the aim of the exercise which they found a bit puzzling at first. Most of the questions focused around:

“what the story should be about, whether it had to about something real or make-believe” (to which I replied that it was to be plausible);

“how many cSquares should they choose?” (to which I systematically responded that it was up to them). The story could portray communication situations that they are aware of in everyday life, either through the media or through personal experience or could exemplify some of the communication theories they had heard of or learned of during the course.

Students then had one week to work on their storyline outside of the class. During the last class, they presented their stories in front of their classmates.. Each group had 10 minutes maximum to stage and tell their story. they could use any type of props and presentation material (powerpoint slides, videos, staging, role plays, etc).

The presentations were not filmed.

The 24 stories constructed from the 74 cSquares collected in 2015 illustrate how students were able to articulate a path among the depictions of communication in order to make convincing statements and narrative about the role of communication in society. For reasons of space, it is not possible to reproduce the entire sets of slides used in the 24 presentations nor to reproduce the stories in their entirety. However, we obtained the written scenarios of the stories which struck us as particularly well articulated, striking or creative. We note that in particular, cSquare 67 proved to be popular since it featured in many of the stories whereas the execution of the drawing is rather tentative, schematic and not particularly striking. This drawing conveyed a popular belief about the social function of communication that captured the imagination of many students. It showed a shepherd holding a staff and using a loudspeaker to call his flock of sheep to attention who then follow him. This is clearly an allegory of the hypodermic syringe or the functionalist-behaviourist theory of the mass media defended by Harold Lasswell (1927) to which Paul Lazarsfeld (1944) brought a nuance by postulating the two-step-flow model of communication which states that people's opinion are more influenced by intermediaries (circles of friends, families, co-workers, opinion leaders). However, later studies by McCombs and Shaw’s on the Agenda setting theory (1972) of the mass media reaffirmed their influence on public opinion. The drawing portrays the unidirectional model of communication as a powerful tool for propaganda and persuasion in the hands of opinion leaders or of the mass media. The flock of sheep here represent the masses who adopt the views of those perceived as opinion leaders rather than form their own.

Underlying this seemingly simple depiction is the psychology of the crowd which has been well studied in behavioural sciences, since the late 19th century (Gustave Le Bon 1895). Fiction and literature have also given us many memorable illustrations. Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar famously portrays the very fickle nature of public opinion which was constantly swayed by the last orator.

Below is a translated and abridged version of two of the most remarkable story lines that were presented in our 2015 storytelling activity using this collection of cSquares.

Communication campaign strategy storyline

Marketing campaign story.

Marketing campaign story.

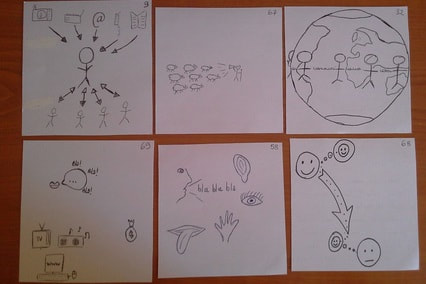

This story is set in the planning stages of an international marketing campaign to launch a fictitious product by a team of communication consultants. This story employed six cSquares to highlight the persuasion-influence function of communication (Figure 2 below). Students artfully and insightfully associated the publicity and marketing “behind-the-scenes” discourse with communication theories which best explained the manipulative ideologies therein.

Stage 1 of the campaign entitled “Know your target population” used cSquare 9 to illustrate Harold Lasswell’s hypodermic needle model of mass communication. However, since the explanatory power of Lasswell’s theory on how public opinion formation was somewhat weakened by Paul Lazarsfeld’s two-step flow communication model, the students supplemented it with this second theory to cater for segments of the target audience that are not directly under media exposure but are more likely to be influenced by intermediaries (opinion leaders, friends, colleagues). This justified their recourse to more than one communication strategy and therefore to more than one theory. Students then used cSquare 67 which they labelled the “mass effect” to illustrate their two-stage communication strategy in order to ensure maximum coverage of their target audience. This drawing served to illustrate how certain brands or messages became successful because they had been adopted by celebrities. By analogy, the shepherd in the drawing is the celebrity or the opinion leader influencing his flock of followers. This is totally in line with our earlier interpretation of this drawing.

Stage two of the campaign strategy entitled “Our objectives” consisted in explaining their communication policy and the expected ROI. Three objectives of the campaign were identified: cognitive, affective, conative which are direct references to Roman Jakobson's well-known six functions of language. Under the heading “How to make the product known”, cSquare 32 was used to explain that although communication is a global phenomenon, it needs to be tailored to specific consumers according to local culture (customs, traditions, beliefs, attitudes). Here again, students gave example of successful brands like Mcdonalds and Apple iPhones whose communication strategies were so successful that their products became indispensable and global household names. On the theoretical level, the students predictably invoked Marshall McLuhan’s prediction that the next set of inventions (from the 1980s) will make the world a “global village”. This corroborates our interpretation of this cSquare which we made previously in our thematic analysis before we heard the students’ storyline.

Under the heading “How to push people to consume”, cSquare 69 was used to explain that communication is associated with money (the drawing shows a mouth saying “bla bla bla”, some ICT devices and a bag of money with the $ sign). Again, this statement was backed up theoretically by a reference made to a quotation by from a well-known french communication scholar, Dominique Wolton who said that “Communication is the art of seduction”. Hence, the objective of the communication campaign is to seduce consumers into buying their new product.

Stage three of the campaign focused on "the means of communication" (form of the message, the devices and media employed). cSquare 58 which shows the five senses (face, mouth, lips, eyes, ears, hand) used in human face-to-face communication was used to convey the fact that communication can be verbal and non verbal. This was also stated verbally in the students' script.

The students then tackled the “Question of the intention” (teleology) in which they illustrated the fact that a message sent with a particular intent may be interpreted in a different way. cSquare 68 was chosen to convey this idea. It shows two sets of faces: the sender of a message and a mirror image of that face smiling (as if it was showing the intent and the mind of the sender) and a second face that of the receiver and a mirror of his face unsmiling, which conveyed the idea that the message was not interpreted in the way the sender meant it to be.

The way in which the students interpreted this drawing showed more depth than our own interpretation of the drawing. via the thematic analysis The students obviously understood better the intent of the author of the drawing (could it be that one of them was the author?). Hence, the storytelling activity can deepen the thematic analysis done by the looking at the drawings in isolation. As examples of how the purpose of a message can be misinterpreted by the target audience, the students cited the case of Benetton brand which specialises in outrageous publicity campaigns that often ended up having a negative effect than the positive one the company had expected.

“The question of feedback” was tackled in the fifth stage. The students correctly analysed its strategic importance in view of the empowering capabilities of web 2.0 technologies which make customers’ voices more audible and powerful. Companies, brands and reputations can be destroyed in minutes by a bad buzz. The students correctly analysed that feedback can be a positive thing in that it can enable an organisation to adjust its message but it can also be negative in the case of bad buzz. The theoretical justification of the importance of feedback in communication is of course Wiener’s cybernetics model which showed that in any system (human, animal or machine) the components of that system are in interaction with one another and their actions are auto-regulated by feedback received from their environment. Wiener defined two types of feedback: positive which accentuates the phenomenon and negative which diminishes the effect expected. cSquare 60 was chosen to illustrate the cybernetic and circular model of communication. Once again, students illustrated the consequences of a negative feedback by citing the case of IKEA who had removed all feminine presence in one of its catalogue destined to Saudi Arabia thereby generating a negative feedback from viewers in the western world.

The story then concluded by recalling three ingredients that are fundamental to a successful communication campaign: choosing one’s target, defining one’s objectives and choosing the adequate means to get the message across as effectively as possible.

Stage 1 of the campaign entitled “Know your target population” used cSquare 9 to illustrate Harold Lasswell’s hypodermic needle model of mass communication. However, since the explanatory power of Lasswell’s theory on how public opinion formation was somewhat weakened by Paul Lazarsfeld’s two-step flow communication model, the students supplemented it with this second theory to cater for segments of the target audience that are not directly under media exposure but are more likely to be influenced by intermediaries (opinion leaders, friends, colleagues). This justified their recourse to more than one communication strategy and therefore to more than one theory. Students then used cSquare 67 which they labelled the “mass effect” to illustrate their two-stage communication strategy in order to ensure maximum coverage of their target audience. This drawing served to illustrate how certain brands or messages became successful because they had been adopted by celebrities. By analogy, the shepherd in the drawing is the celebrity or the opinion leader influencing his flock of followers. This is totally in line with our earlier interpretation of this drawing.

Stage two of the campaign strategy entitled “Our objectives” consisted in explaining their communication policy and the expected ROI. Three objectives of the campaign were identified: cognitive, affective, conative which are direct references to Roman Jakobson's well-known six functions of language. Under the heading “How to make the product known”, cSquare 32 was used to explain that although communication is a global phenomenon, it needs to be tailored to specific consumers according to local culture (customs, traditions, beliefs, attitudes). Here again, students gave example of successful brands like Mcdonalds and Apple iPhones whose communication strategies were so successful that their products became indispensable and global household names. On the theoretical level, the students predictably invoked Marshall McLuhan’s prediction that the next set of inventions (from the 1980s) will make the world a “global village”. This corroborates our interpretation of this cSquare which we made previously in our thematic analysis before we heard the students’ storyline.

Under the heading “How to push people to consume”, cSquare 69 was used to explain that communication is associated with money (the drawing shows a mouth saying “bla bla bla”, some ICT devices and a bag of money with the $ sign). Again, this statement was backed up theoretically by a reference made to a quotation by from a well-known french communication scholar, Dominique Wolton who said that “Communication is the art of seduction”. Hence, the objective of the communication campaign is to seduce consumers into buying their new product.

Stage three of the campaign focused on "the means of communication" (form of the message, the devices and media employed). cSquare 58 which shows the five senses (face, mouth, lips, eyes, ears, hand) used in human face-to-face communication was used to convey the fact that communication can be verbal and non verbal. This was also stated verbally in the students' script.

The students then tackled the “Question of the intention” (teleology) in which they illustrated the fact that a message sent with a particular intent may be interpreted in a different way. cSquare 68 was chosen to convey this idea. It shows two sets of faces: the sender of a message and a mirror image of that face smiling (as if it was showing the intent and the mind of the sender) and a second face that of the receiver and a mirror of his face unsmiling, which conveyed the idea that the message was not interpreted in the way the sender meant it to be.

The way in which the students interpreted this drawing showed more depth than our own interpretation of the drawing. via the thematic analysis The students obviously understood better the intent of the author of the drawing (could it be that one of them was the author?). Hence, the storytelling activity can deepen the thematic analysis done by the looking at the drawings in isolation. As examples of how the purpose of a message can be misinterpreted by the target audience, the students cited the case of Benetton brand which specialises in outrageous publicity campaigns that often ended up having a negative effect than the positive one the company had expected.

“The question of feedback” was tackled in the fifth stage. The students correctly analysed its strategic importance in view of the empowering capabilities of web 2.0 technologies which make customers’ voices more audible and powerful. Companies, brands and reputations can be destroyed in minutes by a bad buzz. The students correctly analysed that feedback can be a positive thing in that it can enable an organisation to adjust its message but it can also be negative in the case of bad buzz. The theoretical justification of the importance of feedback in communication is of course Wiener’s cybernetics model which showed that in any system (human, animal or machine) the components of that system are in interaction with one another and their actions are auto-regulated by feedback received from their environment. Wiener defined two types of feedback: positive which accentuates the phenomenon and negative which diminishes the effect expected. cSquare 60 was chosen to illustrate the cybernetic and circular model of communication. Once again, students illustrated the consequences of a negative feedback by citing the case of IKEA who had removed all feminine presence in one of its catalogue destined to Saudi Arabia thereby generating a negative feedback from viewers in the western world.

The story then concluded by recalling three ingredients that are fundamental to a successful communication campaign: choosing one’s target, defining one’s objectives and choosing the adequate means to get the message across as effectively as possible.

Communication religion satire

The second story is a satire about the power of communication cast as an all powerful religion against a backdrop of Greek mythology. The three students forming this group actually acted this play out in front of their peers. Given its allegorical nature, a summary of the script will lose the essence of the satire. The full translation of this satire is offered below with some of my comments in brown and in curly brackets.

Aside from the six drawings chosen from the collection of cSquares (Figure 3 below), the students added other colourful and striking illustrations culled from the Internet.

Introduction

Since the 20th century, we witness the birth and the lightning ascension of a new religion: Communication. Known since a long time, it has hoisted itself up by dint of information and media to penetrate our beliefs, hopes and lives.

I. Polytheism

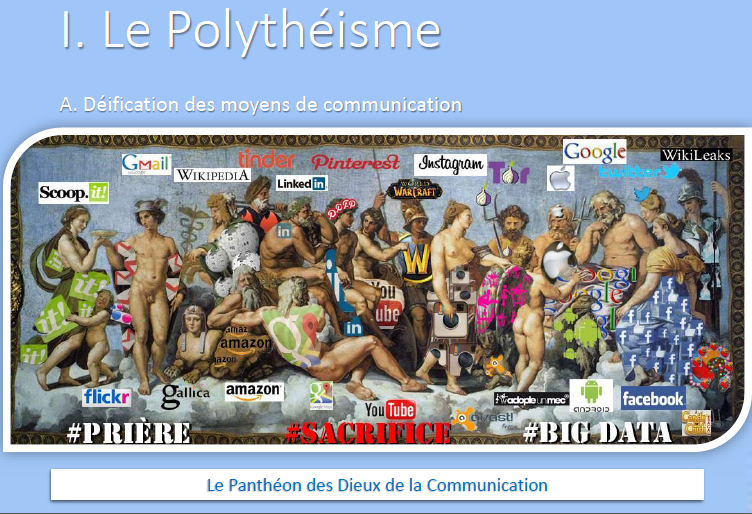

a) Deification of means of communication

On Data-Olympus, all is networks and Google, the Zeus of Internet reigns supreme, surrounded by his brothers Apple (Poseidon) and TOR (Hades), his wife Facebook (Hera), his children WOW (Ares), Youtube (Appollo), Instagram (Aphrodite), Twitter (Artemis), Tinder (Hephaestus)! And let’s not forget his faithful Gmail (Hermes) and the rest of the pantheon!

Our gods have led us to the peak of cybernetics! We communicate with machines and by machines. We love them, we cherish them, we sacrifice our time, our data, our lives to them. We can no longer live without them, and for most of us, we cannot imagine life away from their bosom.

{Students used the image in illustration 1 probably culled from the Internet to illustrate this textual sequence. The apt choice of different Greek gods to represent web technologies and platforms shows the students' knowledge the Greek mythology. Hermes as we know is the messenger god. Some of the students in this group had majored in history and archeology before coming to do the Masters in Communication and Media, thus showing how they tapped into their prior intellectual baggage to reinterpret communication theories and phenomena.}

Aside from the six drawings chosen from the collection of cSquares (Figure 3 below), the students added other colourful and striking illustrations culled from the Internet.

Introduction

Since the 20th century, we witness the birth and the lightning ascension of a new religion: Communication. Known since a long time, it has hoisted itself up by dint of information and media to penetrate our beliefs, hopes and lives.

I. Polytheism

a) Deification of means of communication

On Data-Olympus, all is networks and Google, the Zeus of Internet reigns supreme, surrounded by his brothers Apple (Poseidon) and TOR (Hades), his wife Facebook (Hera), his children WOW (Ares), Youtube (Appollo), Instagram (Aphrodite), Twitter (Artemis), Tinder (Hephaestus)! And let’s not forget his faithful Gmail (Hermes) and the rest of the pantheon!

Our gods have led us to the peak of cybernetics! We communicate with machines and by machines. We love them, we cherish them, we sacrifice our time, our data, our lives to them. We can no longer live without them, and for most of us, we cannot imagine life away from their bosom.

{Students used the image in illustration 1 probably culled from the Internet to illustrate this textual sequence. The apt choice of different Greek gods to represent web technologies and platforms shows the students' knowledge the Greek mythology. Hermes as we know is the messenger god. Some of the students in this group had majored in history and archeology before coming to do the Masters in Communication and Media, thus showing how they tapped into their prior intellectual baggage to reinterpret communication theories and phenomena.}

|

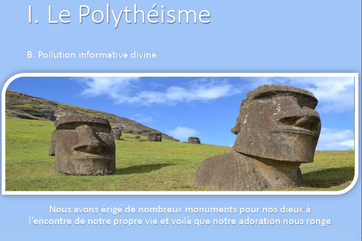

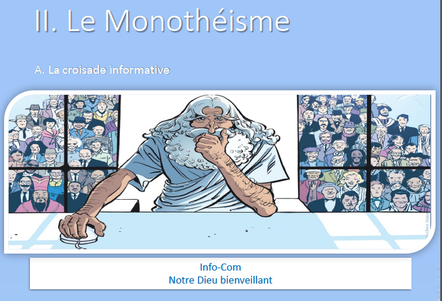

b) Divine informative pollution

Our modern society is in the grips of divine pollution! The gods are so present that they have invaded our dear vital space, our ecosystem. We are no longer in the information village – as McLuhan might have said – but well on planet information. We have erected many monuments to our gods at the expense of our own lives and behold, our adoration is eating away at us. We live, eat and breathe for our gods, but will they save us? II. Monotheist a) The information crusade Since a certain amount of time, the gods have reunified in order to form but one, the unique InfoCom God. For his love, we turned ourselves into a flock of sheep following his priests, priestesses or his most fervent disciples blindly. We call them journalists, communicators, or simply opinion relays. We are waging a crusade against the slowness of transfer and the lack of information and communication. New Bernard de Clairvaux [1] are leading us, but will they lead us to our destruction during this second crusade? b) The informative reform Our crusades drive us more and more into illumination and informational and communicational extremism! Our priests preach to us thus:

[2] A latin expression for «Step back Satan». See http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vade_retro_satana [3] The act of killing a god. {This whole sequence once again shows the students level of erudition and knowledge of ancient history and mythologies}. But voices are raised today, advocating the return to the true belief (knowing how to read). The reform is on, rallying many men and women in the worthy calvinist tradition that demands a return to the origins: to a more organised and structured world. Religious obscurantism is being transformed and phased out. {Illustration 4 which is again captioned "Monotheism II" and "informative reform" has as bubble speech the following monologue by the Info-Com Lord: Have humans not yet finished their foolishness? I'm on strike since the season 1 of Secret Story anyway!"}. III. Animism a) Return to the human But let’s go back to basics, we all know this credo of the Palo Alto school “we cannot not communicate”. Yes, all is communication, but it comes first from us! Our body emits and receives information. We have to be aware that our communication towards others is also sensory. It is what makes communication more meaningful and different from simple contact. Think about it: try to remember all the people you spoke to. With how many did you have meaningful communication? {This sequence is illustrated by the image entitled "Humanism III" in illustration 5.} b) Union of information, communication to the world We all need to find ourselves and to share more concrete link that is less virtual and turned towards reality. We do not need God Google and co. We do not need infocom, the unique God. We are the divine communicator, the divine informing, the divine mediatic! We do not need external gods. We are everything and everything is us! We are God! The ancient gods must fall. We shall not sacrifice ourselves anymore for them. We must subjugate them and use them for ourselves and for others like us: for our earth. {To illustrate this sequence, the students used the same title of "Humanism III" in illustration 6 but with a different image in which we witness the triumphal return of true communication, that which is between humans, not mediated by computers nor supplanted by softwares that tell us what to do or think. The all-powerful Google is finally vanquished and put in a cage (or is it a cart?).} Conclusion We are thus living in a world invaded by information but also by noise where we only swear by ICTs. In this world where mail has replaced letter, selfies postal cards, there is still hope because on the Internet, sharing resists capitalism as Jeremy Rifkin explained. But we are offering ourselves to social media for which we become “consumer-producer” and we spend time there. By the way, the American magazine “Time” offers a tool on the Internet allowing us to estimate the time lost on Facebook. As an example is worth a thousand words, since 14th april 2008, I have lost 158 days of my life on Facebook. And you? The END |